Normandy - 6th June 1993

Ranville military cemetery. Forty-nine years earlier thousands of allied soldiers had landed on the beaches of Normandy to release Europe from the domination of Nazi Germany. Within a few days of the Invasion they had enough bodies to fill this cemetery and more like it across the province, all because of one man’s megalomania and a nation’s militaristic pride.

I was there because I had to experience the human side of war. I have studied military history from childhood; the tactics, logistics, strategies and mechanics, even the reasons why it happens, but the man waiting in a landing craft to rush into a hail of bullets with minutes to live was a mystery to me.

My Grandfather - who managed to get invited to both Dunkirk and Normandy - had told me about his war, but I was young and the stories were designed to amuse and highlight the lighter side of his campaigns. Maybe that was his way of blocking out the bad emotions, the fear and the pain he must have felt, but for whatever reason, I had no clear concept of the men who did the fighting or dying and without that there can be no clear understanding of the futility of war and the value of peace.

Not that I am suggesting that we should not have fought the war of liberation. There can be no doubt that the Allies had no alternative to total war in the summer of 1944. However, looking at the rows of white tablets marking the graves on a hot summer day nearly half a century later, it was hard not to condemn the British and French politicians in 1938 who allowed the German madman to walk into Czechoslovakia when we could have put enough men into the field to crush all his insane ambitions at birth.

It is of course easy to be judgmental in hindsight, but Churchill had a clear vision of events in 1936 when Germany reoccupied the Saar. Recent European history should have taught those inadequate, posturing leaders the strength of will within German culture that made conflict inevitable. By delaying the decision to stand, these men condemned millions more to die. Santayana wrote: "Those who do not learn from history are condemned to repeat it". Never was that more poignantly demonstrated than in the causes and effects of the Second World War.

That is why I felt a tinge of bitterness as I stood there in the sweltering heat, amongst the living and the dead listening to the service for the fallen.

Standing beside me was George Evelyn Wood. Ex Royal Marine commando and general old reprobate of Coggeshall parish. He was the reason I was there and the bridge between those soldiers of the past and my desire to gain a sense of human history that I can touch.

George had a hard war by anyone's standards. After a difficult landing, which saw 47 RM. Cdo take high casualties, they attacked and captured their main objectives without support from the Americans pinned down on Omaha beach. The German counter attack lead to George and most of his comrades being captured and interned in a POW camp until the end of the war nearly a year later.

His stories of those times, recounted over a few drinks in convivial company have come to be very special to me. I can't feel these experiences in a book, but I can see them in his eyes, in his sweating palms and the fading tattoos on his hand and arm. I can hear his voice changing tone as he described a German NCO's luger being shoved into his guts as the man George had just shot died by inches on the floor in front of them. I can close my eyes and see the selfless acts of heroism that the situation engendered, not as the propagandists would have us believe out of bravery, but out of resignation to the situation and an unwillingness to accept his own or anyone else's death without a struggle.

So to meet George at the remembrance service was a privilege and a part of the leaming process for me.

We stood side by side near the memorial erected in the centre of the cemetery. Around us stood the veterans, arbitrary survivors of the horrifying events the remembering of the dead brought into focus. Around us the locals mingled with friends and relatives of the comrades in arms as Binyon’s words were barked out over the assembly by a retired officer of the paratroopers:

"They grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them. "

My eyes filled with tears as I felt the sense of history I had been searching for. The gravestones told it all; age 19, age 20, age 21... Frozen in time and in history. Ripped away from us, no more to feel the caress of the woman they love or hear their children's laughter or argue good naturedly over a pint with their friends. Their allotted span taken from them, stolen by events and people they neither understood nor knew.

It wasn’t Binyon’s "For the Fallen" that I had in mind but another of his poems:

... Know’st thou not that her tender heart

For pain and very shame would break?

O World, be nobler, for her sake!"

Normandy 5th - 7th June 2014

And then in June 2014 I went back to re-trace my steps. I am not sure exactly why, but I think to honour my own fallen. George had died around 4 years after our trip and Keith Bale, a close friend who had accompanied me the first time around, had died a few years after that. Maybe their ghosts were calling me to make some kind of pilgrimage and maybe my sense of history recognised this was the last chance to rub shoulders with the survivors of this epic event.

The vets, 'the human side of war' as I called them at the time, are thinning out rapidly in numbers. Their effort and sacrifice increasingly marginalised in a first world more obsessed with its present than its past or future.

We have to remember that European peace is a privilege not a right. If we forget that, it can all unravel very quickly, and if that happens the shadows in those vets haunted eyes and the rows upon rows of white tombstones will be the consequence.

It is our past, but in honouring all that sacrifice, for all that they gave, let it not be our future...

Binneyink - May 2017

-

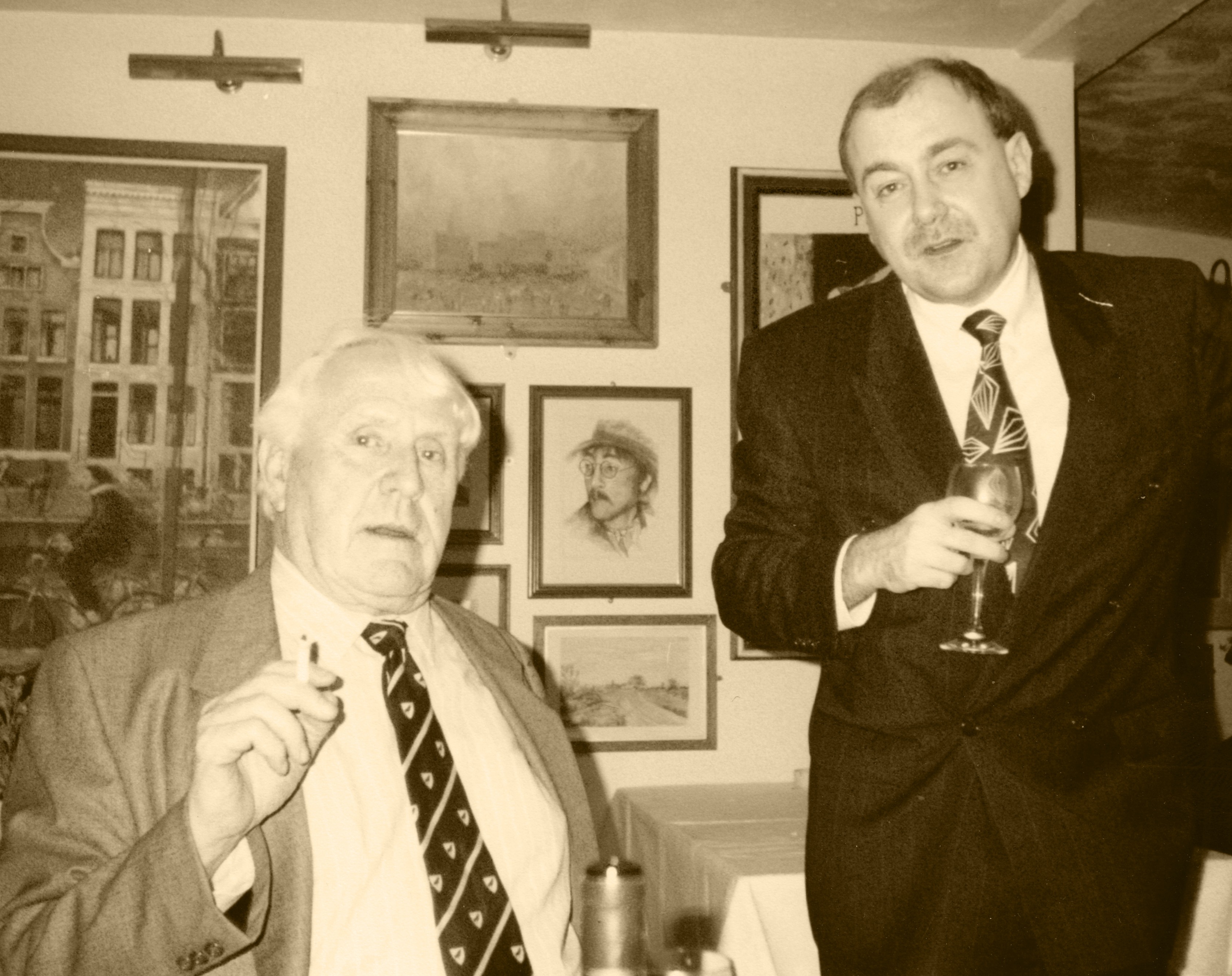

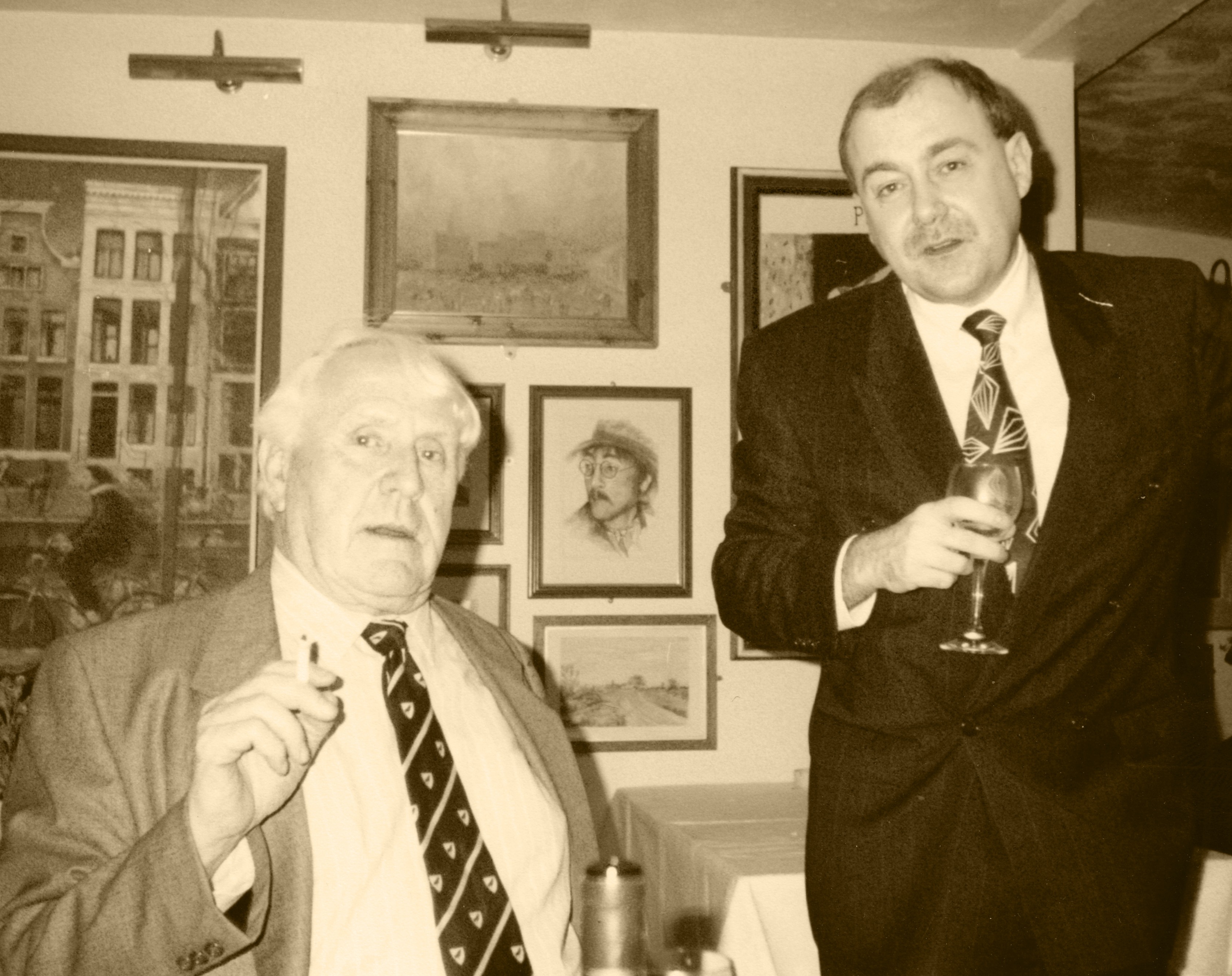

George Wood (r) - RM Cdo & Party Animal - 1922-97

47 RM Cdo - HQ Troop - Service No: CH/X103876

George Wood (r) - RM Cdo & Party Animal - 1922-97

47 RM Cdo - HQ Troop - Service No: CH/X103876

-

George Wood - Peter Case - Baumans 311291

George Wood - Peter Case - Baumans 311291

-

Port-en-Bessin Memorial 7 June

Port-en-Bessin Memorial 7 June

-

Poppies... P-e-B 7 June

Poppies... P-e-B 7 June

-

Spitfires straffing crowd Ranville Display 5 June

Spitfires straffing crowd Ranville Display 5 June

-

Parachute Drop DC3 - Ranville Display - 5 June

Parachute Drop DC3 - Ranville Display - 5 June

-

Unopposed Landing - Ranville Display - 5 June

Unopposed Landing - Ranville Display - 5 June

-

Service Personnel - Ranville Display 5 June

Service Personnel - Ranville Display 5 June

-

Ranville Cemetery Church - 5 June

Ranville Cemetery Church - 5 June

-

Colours at Ranville Cemetery - 5 June

Colours at Ranville Cemetery - 5 June

-

Vets & families at Ranville Cemetery - 5 June

Vets & families at Ranville Cemetery - 5 June

-

The day after the show - Sword Beach 7 June

The day after the show - Sword Beach 7 June

-

Entrance to Port-en-Bessin Cemetery 7 June

Entrance to Port-en-Bessin Cemetery 7 June

-

HMS Bulark & 1944 uniform - P-e-B Cemetery 7 June

HMS Bulark & 1944 uniform - P-e-B Cemetery 7 June

-

RM47 Cdo Memorial Service P-e-B Cemetery - 7 June

RM47 Cdo Memorial Service P-e-B Cemetery - 7 June

-

Vets arriving up the hill P-e-B Cemetery 7 June

Vets arriving up the hill P-e-B Cemetery 7 June

-

Port-en-Bessin with HMS Bulwark offshore 7 June

Port-en-Bessin with HMS Bulwark offshore 7 June

-

47 RM Cdo's D-Day Immortalised - P-e-B - Cemetery

47 RM Cdo's D-Day Immortalised - P-e-B - Cemetery

-

47 RM Cdo 70th Anniversary - P-e-B Cemetery 7 June

47 RM Cdo 70th Anniversary - P-e-B Cemetery 7 June

-

47 RM Cdo Memorial - P-e-B 7 June

47 RM Cdo Memorial - P-e-B 7 June

-

HMS Bulwark - P-e-B 7 June

Assault Ship that brought 42 RM Cdo to the ceremony

HMS Bulwark - P-e-B 7 June

Assault Ship that brought 42 RM Cdo to the ceremony

-

Jeep & Dodge trucks - P-e-B 7 June

Jeep & Dodge trucks - P-e-B 7 June

-

Rare sighting of a Sherman BARV 'Sea-Lion' - P-A-B

Beach Armoured Recovery Vehicle for pulling stuck tanks out of the drink

Rare sighting of a Sherman BARV 'Sea-Lion' - P-A-B

Beach Armoured Recovery Vehicle for pulling stuck tanks out of the drink

-

CSM on Parade - P-e-B- 7 June

CSM on Parade - P-e-B- 7 June

-

There's always a piper at these things - P-e-B

There's always a piper at these things - P-e-B

-

Vet at P-e-B Cemetery 7 June

Vet at P-e-B Cemetery 7 June

-

47 RM Cdo Vet at P-e-B Cemetery 7 June

47 RM Cdo Vet at P-e-B Cemetery 7 June

-

Now & Then - P-e-B Cemetery 7 June

Now & Then - P-e-B Cemetery 7 June

-

DUKW - Sword Beach - 7 June

DUKW - Sword Beach - 7 June